Meaningful Maps

Places are part of our identity. Places we inhabit in childhood, and the kinds of experiences we have there, remain in our memory and influence our future dispositions as adults. Early, positive, experiences in outdoor settings can even contribute to children developing pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours adults according to Significant Life Experiences (SLE) research (Catling et al 2010).

Research into children’s Meaningful Maps by Vujakovic et al (2018) indicates how children give meaning to different aspects of their environment and especially, how much they value their home places. We come to know places in cognitive and emotive ways, and young children have a good deal of geographical imagination and experience in their head already when they come to school. Exploring what children know and think about their local area, is a powerful, beginning context for learning at any time, but especially so now because of the pandemic, as patterns of everyday live have changed so dramatically in recent memory. Access to places, routes and range have changed because of ‘lockdown’, and many of our favourite and familiar places have been out of bounds for months at a time. These activities can provide a helpful outlet for children to talk through and reflect on changes in their locale and how they feel about them.

Teacher Notes

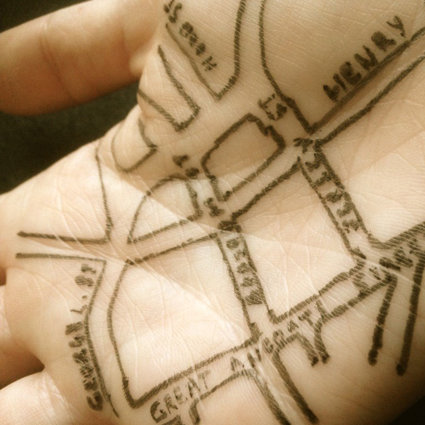

Mental mapping is a term given to maps that exist in our mind’s eye; spatial recollections which can be recalled to either help us navigate, describe or talk about places we envisage or have experience of. These maps can be written, drawn and / or modelled: created from memory, they offer insights into what children know and think about the places they describe and recall, allowing them to respond from heart and mind. Giving children opportunities to talk about and annotate their maps also encourages use of geographical vocabulary in meaningful contexts.

Maps of this kind reveal not just what children know and understand about their local area but also, the level of their skill in mapping techniques and conventions. Mental mapping can be used diagnostically too, to reveal geographical misconceptions, which can then be challenged and corrected. These maps can be helpful for the teacher in planning locality fieldwork as they provide a valuable insight into what is known, or not, about the local area.

Mental maps also offer a great way in to understanding more formal mapping techniques as pupils can compare what they have drawn, with the way reality has been mapped using mapping techniques such as that from Ordnance Survey cartography.

Key Questions

What do we mean by local?

What is your local area like?

What different features are there?

Which are your favourite places?

Where do you like to play / go to the shops / meet friends etc?

Which places aren’t you allowed to go?

Why are these places special to you?

Presentation: Meaningful Maps Lesson 3 (see PPT Stay Home 3 Meaningful Maps)

Getting Started

Discuss where children live and what their local area is like. You could ask how we define ‘local’ and what it means. Take suggestions from children and help them think about this. One way to explain it for example, might be to think about the places we regularly visit and go to where we live.

Mental maps

Ask children to draw or make a map showing their local area, including their home, and places that matter to them. Encourage them to annotate their map with comments or to add a separate, written explanation. Children could include descriptive phrases and short anecdotes; they might add not just formal names of places in the locality but their own invented names for secret play areas or features that have special significance to them. Children do not just have to include places they have experienced first-hand; they could also add areas that they know about, but haven’t been to because they are dangerous, out of bounds or inaccessible.

Talking maps

Ask children to take turns explaining their map with a partner. What similarities and differences do they note? Do their maps of the ‘local’ overlap, or do they show completely separate areas? How do the activities they do in their local area compare? What do they like about the way each other has drawn their map?

Formal mapping

Using digital software such as Digimap for Schools, younger children could use aerial imagery and formal mapping to locate and identify some of the features shown in their maps. Older children could go on to create a formal map of their local area and significant places in it, using the information on their hand-drawn map. They could for example:

-

Locate and label their home.

-

Locate and label other features shown such as school, shops, park etc.

-

Add their favourite play areas.

-

Use emoticons to show how they feel about places: happy, sad, excited, scared etc.

-

Highlight and measure routes.

-

Highlight and measure their range.

Discuss how their memory map compares with the formal map of their local area. You could create a class map of features with shared significance.

My geography glasses

Give children an outline of a pair of glasses and ask them to draw or write the features they have in the local area in one lens. In the other lens draw or write the activities that they like to do in their local area. Discuss the connection between the built and physical features of an area and what you can do there. For example, you can only picnic in the park if you have a park near you, go swimming if you are near a pool or a body of water suitable for swimming, go to the cinema if you have one nearby. You could adapt this for younger children to use with features in the school grounds.

Fieldwork

Use information form the maps to plan some locality fieldwork, visiting some of the places shown, or perhaps targeting important local features not well-known. Use this as an opportunity to gather more information, such as taking photographs, of significant and / or popular features.

Taking it further

Children could use formal mapping or hand -drawn techniques to create a local landmark trail of ‘wonders’ using features identified by the children as being of note. Add QR codes to maps with sound files of children talking about why these landmarks are special.

Vocabulary (See Stay Home 3 Meaningful Maps Vocabulary)

NC links KS1 and 2 Geography

KS1

Pupils should:

understand basic subject-specific vocabulary relating to human and physical geography and begin to use geographical skills, including first-hand observation, to enhance their locational awareness.

-

use basic geographical vocabulary

-

use aerial photographs and plan perspectives to recognise landmarks and basic human and physical features; devise a simple map; and use and construct basic symbols in a key

-

use simple fieldwork and observational skills to study the geography of their school and its grounds and the key human and physical features of its surrounding environment.

KS2

Pupils should:

describe and understand key aspects of:

human geography, including: types of settlement and land use,

-

use the eight points of a compass, four and six-figure grid references, symbols and key (including the use of Ordnance Survey maps) to build their knowledge of the United Kingdom and the wider world

-

use fieldwork to observe, measure, record and present the human and physical features in the local area using a range of methods, including sketch maps, plans and graphs, and digital technologies.

Links to other Areas of learning

English: writing about and annotating maps

Mathematics: measuring routes and areas

History: opportunities to identify and learn about local features of significant historical interest and for pupils to talk about their own remembered memories.

About the Project: stories

During these extraordinary times, our homes have never been more important. Through the ‘Stay Home’ collecting project the Museum of Home in East London is inviting people across the UK and beyond to submit images, written words, audios and videos of their experiences of home during the COVID-19 pandemic.

About the Project: maps

The Mapping Home strand of the ‘Stay Home’ project is asking children and young people to draw a map of home. By asking them to express these spaces on paper, we hope to gain a better understanding of how their experience of the home space may have changed during the COVID-19 restrictions. The maps act as a tool for supporting children and young people in sharing knowledge of their unique experiential expertise of COVID-19 onto paper.

References

Catling, S, Greenwood, R. Martin, F, Owens, P. (2010) Formative experiences of primary geography educators, International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 19:4, 341-350,

Vujakovic, P., Owens, P. & Scoffham, S. (2018) Meaningful Maps: What Can We Learn About ‘Sense of Place’ From Maps Produced by Children? SoC BULLETIN Vol 51 pp.9-19

Other Links

My Geography glasses | Digimap for Schools Resource Centre (edina.ac.uk)

Submit your maps

Please submit your Stay Home maps through www.rgs.org/stayhome – we are really interested to see what you have created!