By Danny Dorling, University of Oxford

Why bother?

Working with the media is optional for academic geographers. Most will hardly ever engage with newspapers, magazines, go on radio or television. Their footprint on social media will be small, or not existent at all. This is all as it should be. It would be impossible for many of us to be much involved. There is simply not enough space in the pages of newspapers or magazines, not enough time in the schedules of radio or television programmes, and no huge unguided audience out there aching to read your blog posts, hear your podcasts, or retweet your thoughts.

Occasionally, however, you may have something you really want other people to know about, a book you have written or a finding in an article. Even more occasionally, journalists may come to you and you might wonder whether you should engage. Many academics are extremely trepidatious about having their words taken out of context. Some may even think that what they do should be confined to the ivory tower because it is simply too complex for other people to understand. Others are a little more open and curious.

Academic training in nit-picking phrases and worrying greatly about the nuance of arguments is not a particularly good starting point for engaging with the wider media. You cannot expect what you want to say to be conveyed exactly as you would like it to be. Write an article for a newspaper, for example, and you have absolutely no say over the headline that is put above that article. This alone can be enough to put many academics off; but it is the price you have to pay if you want more than a few dozen people to know what you have to say.

Some of the dos and don’ts

Look up the published work of any journalists who contacts you before replying. Don’t talk to journalists who write nasty articles – you won’t change their views and they are very likely to twist yours. Give preference to newspapers and magazine that are free-to-read on the web, or that at least allow a few articles to be read a month for free.

Do make you main point early on and clearly. Don’t believe that you will get more than a few seconds to talk on a 24 hour TV news programme or radio show. If you become confident enough, chose live media over pre-recorded programmes. The producer can’t edit out your key point if you are live.

Don’t publish, tweet, retweet, ‘like’, say or claim anything that you would not be happy defending years from now. Nothing in the media ever disappears (it can be found in web archives). Don’t be afraid of being boring, the worst that can happen is that they don’t ask you back again. If you do make a mistake, just admit to it – this is so rarely done it is refreshing.

What is the worst that can happen?

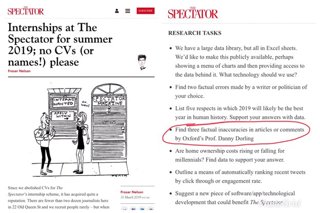

In March 2019 the editor of the Spectator magazine published an advert for internships in his magazine. A copy is below. I did ask him, but he never sent me any of the successful answers to his fourth question, which is a pity as I must have made many mistakes. I suspect that people who want to be interns at the Spectator are just not very good at spotting them.

I joke about this, and in a way it is quite an honour for a human geographer, rather than a political scientist, economist or sociologist to be singled out in this way. But this is the kind of thing that worries academics and it is done to try to dissuade them from speaking out, or to imply that what they find must be riddled with errors, because it suggests that otherwise the worldview of the Spectator editor is misguided.

Sometimes what appears to be bad is not. Later on in 2019 I wrote a paper published in a very obscure academic journal. Unbeknown to me, a journalist at the Times Higher saw it and wrote a summary under the headline ‘Geography seen as “soft option” by “posh” students, warns Dorling’. Then a dozen British newspapers wrote their own version of the story under a title akin to ‘posh and dim’. I was a little annoyed that they used the word dim (I never had), but as a means to let other geographers know that geography had a problem - it was effective. Many of my colleagues responded angrily, until they saw the data. In 2019 human geography was the UK university degree which took the most students from the most affluent neighbourhoods and the fewest from the poorest. No other degree was as posh. I suspect that when the latest, post-pandemic data is analysed this will no longer the case. However, it will never be possible to prove if those newspaper stories put some posher students off applying, due to the fear of being labelled dim.

How to cite

Dorling, D. (2023) Engaging with the media. Communicating research beyond the academy. Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) Guide. Available at: https://doi.org/10.55203/WIKF7987

About this guide

There’s a long tradition of geographers communicating research ‘beyond the academy’ - to policy, to publics, to young people, to school teachers - whether to recruit students, for career development, critical praxis and activism, or requirements of funders to document ‘impact’. Ten years ago we published the Communicating Geographical Research Beyond the Academy guide. It sought to bring together and share collective experience and learning, from within and beyond the academy. Today, there’s ever more opportunities and modes and media with which to do this. While many of the points made – about audience, about access, about brevity and the use of plain English – still stand, this collection covers these already familiar issues as well as bringing new perspectives to encourage readers to reflect on motives, means and methods and to illuminate examples of good practice.